It was the afternoon of Thursday 15 February 1894. Martial Bourdin, a 26-year-old Frenchman, left his lodgings in Fitzroy Street, west of London’s Tottenham Court Road. He dined, then walked to the tram terminus at Westminster Bridge, near the Houses of Parliament. There, he climbed aboard one of the horse-drawn trams which ran every few minutes, buying a through ticket all the way to the end of the line at East Greenwich.

A little later, two of the Royal Observatory assistants – William Thackeray and Henry Hollis – were at work in one of the computing rooms, at the top of the hill overlooking the northern reaches of Greenwich Park. Also on-site at the Observatory besides the assistants was the gate porter, William McManus. All three men heard the explosion. Smoke was seen rising from the trees near the Observatory’s front terrace. McManus ran towards the explosion site, seeing Thackeray and Hollis do likewise.

First on the scene, though, were two local schoolboys. At the site of the explosion they found a man, later identified as Martial Bourdin, kneeling on the path by the railings, perfectly still. His head was bowed. The Park keeper on duty that afternoon was next to arrive, followed by McManus, Thackeray and Hollis. At that moment, Bourdin was seen to sink to the ground. The witnesses had by now discovered that the man’s left hand had been blown off; sinews and tendons were hanging down out of the bloody stump. He had a massive wound in his stomach, out of which some of his intestines were spilling, and he had a hole under his right shoulder blade with bone protruding. The gathered party took Bourdin to hospital where he died twenty-five minutes later from shock and loss of blood. He never said what had happened.

McManus, Thackeray and Hollis returned to the Observatory and performed a search of the area between its buildings and the path nearby, where Bourdin had been found. It was a gruesome experience. They found many fragments of his hand, including a two-inch piece of blackened finger-bone. Blood and clothing fragments littered the scene and, the following day, detectives discovered pieces of tendon wrapped around nearby railings, and two knuckle-joints from Bourdin’s left thumb. Martial Bourdin, an anarchist terrorist, had accidentally blown himself up with a bomb right outside the Observatory buildings.

This is an abbreviated extract from Ruth Belville: The Greenwich Time Lady, by David Rooney, published by the National Maritime Museum, 2008 ISBN 978-0-948065-97-2.

Friday, 13 February 2009

Thursday, 5 February 2009

Staff of the ROG in 1894

Astronomer Royal

William Henry Mahoney Christie

Chief Assistant

Herbert Hall Turner (retired 28 February 1894) and Frank Watson Dyson (succeeded 1 March 1894), responsible for general superintendence of all the work of the Observatory, with full power to act in the absence of the Astronomer Royal

First Class Assistants

George Stickland Criswick (photographic mapping of the heavens)

Thomas Lewis (time-signals and chronometers)

Edward Walter Maunder (spectroscopic and solar-photographic observations and reductions)

William Carpenter Nash (magnetic and meteorological branch)

William Grasett Thackeray (miscellaneous astronomical computations and meridian zenith-distance reductions)

Second Class Assistants

Walter William Bryant (transit-reductions and time-determinations)

Andrew Claude Crommelin (altazimuth and equatorial computations)

Henry Park Hollis (library and manuscripts, longitude reductions, miscellaneous correspondence)

(and two vacancies)

Clerk

Henry Outhwaite (from 21 May 1894)

Computers

12 astronomical branch

2 astrographic branch

4 spectroscopic and solar-photographic branch

5 magnetic and meteorological branch

Other staff

Gate-porter, watchman, gardener, foreman of works, 2 carpenters, 1 or 2 labourers, skilled mechanic and his assistant, charwoman.

William Henry Mahoney Christie

Chief Assistant

Herbert Hall Turner (retired 28 February 1894) and Frank Watson Dyson (succeeded 1 March 1894), responsible for general superintendence of all the work of the Observatory, with full power to act in the absence of the Astronomer Royal

First Class Assistants

George Stickland Criswick (photographic mapping of the heavens)

Thomas Lewis (time-signals and chronometers)

Edward Walter Maunder (spectroscopic and solar-photographic observations and reductions)

William Carpenter Nash (magnetic and meteorological branch)

William Grasett Thackeray (miscellaneous astronomical computations and meridian zenith-distance reductions)

Second Class Assistants

Walter William Bryant (transit-reductions and time-determinations)

Andrew Claude Crommelin (altazimuth and equatorial computations)

Henry Park Hollis (library and manuscripts, longitude reductions, miscellaneous correspondence)

(and two vacancies)

Clerk

Henry Outhwaite (from 21 May 1894)

Computers

12 astronomical branch

2 astrographic branch

4 spectroscopic and solar-photographic branch

5 magnetic and meteorological branch

Other staff

Gate-porter, watchman, gardener, foreman of works, 2 carpenters, 1 or 2 labourers, skilled mechanic and his assistant, charwoman.

Wednesday, 4 February 2009

Women at the Royal Observatory

There was a brief experiment of employing women at the Observatory between about 1891 and 1895. They were employed as 'supernumary' computers, in other words in non-permanent roles. These positions had traditionally been take up by boys coming straight from the local schools. Christie had been concerned about the quality of the candidates he received in a time when astronomy and the calculations it involved were increasingly complex, and was occupied with trying to get the Admiralty to agree to the expansion of the permanent workforce and promotion of the best computers (see notes page on Christie's staffing scheme). While the Admiralty dithered, the idea of hiring women was a useful stop-gap as they could be paid at a very low rate despite having excellent qualifications. Women with ambitions in the world of astronomy did jump at the chance, although some were unimpressed by the wages. Like Christie's other computers, these women were trained to make observations with the Observatory's important instruments.

It is not clear why this experiment was not continued beyond the mid-1890s. Perhaps no more women put themselves forward, or perhaps Christie felt that his staffing reforms meant that he now had enough competent male computers. It was not until after the Second World War that women began to be employed on a more regular basis.

Tuesday, 3 February 2009

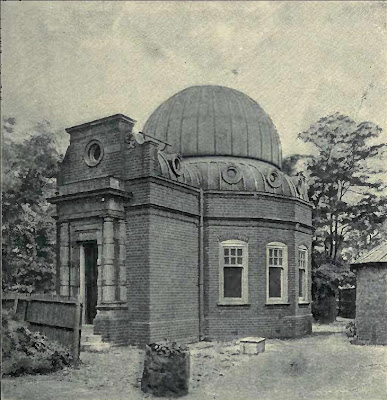

Altazimuth Pavilion

The Altazimuth Pavilion was completed in 1896, having been designed by William Christie and William Crisp. It's design was in keeping with that of the New Physical Observatory, which was in the process of being built. It is named after the altazimuth telescope that it was built to house, an instrument designed to measure both altitude (position above the horizon) and the azimuth (position east along the horizon) of celestial objects. It was also known as the Universal Transit Circle and replaced the earlier altazimuth designed by George Biddell Airy. Christie's instrument no longer survives and the dome now contains a photoheliograph, a telescope used to photograph the sun.

Sheepshanks Equatorial

The Sheepshanks Equatorial is a 6.7-inch refracting telescope with an object glass (OG) by Cauchoix of Paris and mounting by F. Grubb. The OG was donated to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich in 1837 by Richard Sheepshanks (1794-1855), an astronomer who was then Secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society. It was used regularly for the observation of comets, occultations, double-stars and planetary measurement. It was placed in the South Dome, originally built for the Shuckburgh telescope in 1813. This dome can still be seen, just to the east of the Prime Meridian and the Airy Transit Circle. The telescope remained in this position until it was moved to the Altazimuth Pavilion in 1963 and it is now in the museum's stores. See the National Maritime Museum's Collections Online for a more detailed description of this telescope.

The Board of Visitors to the Royal Observatory

The Board of Visitors were, essentially, inspectors of the observatory who visited annually in order to examine the buildings, instruments and work done over the previous year. George Biddell Airy, the 7th Astronomer Royal, began the tradition of delivering a report at each Visitation.

Originally set up by the warrant of Queen Anne in 1710, the Board of Visitors initially consisted of the President and selected Fellows of the Royal Society. They did not, in their early years, meet regularly. In 1830 the composition of the Board was changed and was thereafter made up of the President of the Royal Society and 5 FRS, the President of the Royal Astronomical Society and 5 FRAS, the Plumian Professor of Astronomy from Cambridge and the Savilian Professor of Astronomy from Oxford. In the 1850s the Hydrographer of the Navy also became an ex officio member of the Board.

Originally set up by the warrant of Queen Anne in 1710, the Board of Visitors initially consisted of the President and selected Fellows of the Royal Society. They did not, in their early years, meet regularly. In 1830 the composition of the Board was changed and was thereafter made up of the President of the Royal Society and 5 FRS, the President of the Royal Astronomical Society and 5 FRAS, the Plumian Professor of Astronomy from Cambridge and the Savilian Professor of Astronomy from Oxford. In the 1850s the Hydrographer of the Navy also became an ex officio member of the Board.

In practice the Board of Visitors often acted to back the Astronomer Royals' requests for funds from the government, but the terms of the warrant gave them the power to direct the observing programme if they wished.

Thursday, 29 January 2009

The Lassell Dome and Lassell Telescope

The Lassell reflecting telescope, which had a 24-inch aperture and 20-foot focal length, was built in 1847 for William Lassell (1799-1880), a businessman and astronomer who lived in Starfield near Liverpool. With this telescope Lassell discovered Triton, Neptune's satellite in 1846. It was presented by his daughters to the Royal Observatory in 1883 and it was mounted in this newly-built, 30-foot dome, known as the Lassell Dome. The low-level structure was demolished in the 1890s to make way for the New Physical Laboratory, which reused the dome itself. The dome can therefore still be seen atop the Royal Observatory's South Building.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)